Lazy eye, also known as amblyopia, is a common vision problem that affects both children and adults. It occurs when the brain favors one eye over the other, leading to decreased vision in the neglected eye.

Traditional treatments involve patching the stronger eye to force the weaker eye to work harder, but a new cure for lazy eye is on the horizon. Researchers are making significant progress in understanding and treating this condition, giving hope to millions of individuals affected by lazy eye.

Understanding Lazy Eye

Lazy eye typically develops in childhood when the visual system, specifically the brain-eye connections, are still developing.

It occurs due to various reasons, such as a difference in the refractive errors between the eyes or misalignment (strabismus) of the eyes. If left untreated, lazy eye can lead to permanent vision loss and even blindness in the affected eye.

Current Treatment Options

For decades, the standard treatment for lazy eye has been patching. This involves covering the stronger eye with an adhesive patch, forcing the brain to rely on the weaker eye.

Patching stimulates the connections between the brain and the weaker eye, promoting visual development. However, the effectiveness of patching depends on the age at which treatment begins and the severity of the condition. Younger children tend to respond better to patching compared to older individuals.

Aside from patching, other treatments include atropine eye drops, which temporarily blur the vision in the stronger eye, and eyeglasses or contact lenses to correct refractive errors.

These interventions aim to provide a clearer image to the weaker eye, stimulating its visual development.

The Limitations of Current Treatments

While existing treatments can be effective, they have certain limitations. Firstly, compliance with patching can be challenging, especially in children who may resist wearing the patch.

The success of patching also depends on the dedication and involvement of parents or caretakers.

Additionally, treatment outcomes may not be optimal in cases where the condition is detected late. The brain-eye connections become less flexible with age, making it harder to train the weaker eye to improve its vision.

As a result, some individuals may experience persistent vision problems even after treatment.

Advances in Lazy Eye Treatment

Researchers have been working tirelessly to develop new and more effective treatments for lazy eye. One promising approach is the use of visual training programs and video games designed to stimulate the weaker eye.

These programs employ various techniques, such as contrast enhancement and binocular training, to encourage the brain-eye connections to improve.

Another area of research focuses on non-invasive brain stimulation techniques, such as transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), that aim to modulate the brain activity associated with lazy eye.

Preliminary studies have shown encouraging results, with improved visual acuity and stereopsis (depth perception) observed in some individuals.

Gene Therapy for Lazy Eye

Exciting breakthroughs in gene therapy also offer hope for individuals with lazy eye. Scientists have identified specific genes associated with the development of lazy eye and are exploring ways to modify their expression or function.

By utilizing viral vectors or other delivery systems, researchers can introduce corrective genes directly into the eye, aiming to restore normal visual function.

Although gene therapy for lazy eye is still in its early stages, early experiments on animals have shown promising results. Human trials are currently underway, and researchers are optimistic that this approach may revolutionize the treatment of lazy eye.

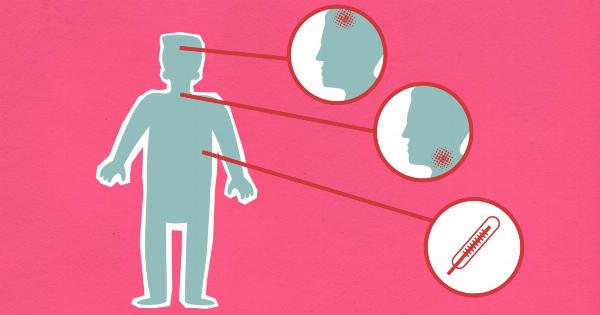

The Importance of Early Detection and Treatment

Regardless of the advancements in lazy eye treatments, early detection and intervention remain crucial for optimal outcomes. Routine eye examinations, especially in children, can help identify lazy eye and other vision problems at an early stage.

The earlier the treatment begins, the higher the chances of successful visual rehabilitation.

Parents should be aware of the common symptoms of lazy eye, including poor depth perception, squinting, and an inclination to use one eye more than the other.

If any of these signs are detected, it is essential to consult an eye care professional promptly.

Conclusion

The future looks promising for those affected by lazy eye, with ongoing research efforts aiming to provide better and more effective treatment options.

Whether through visual training programs, non-invasive brain stimulation techniques, or gene therapy, advancements in the field offer hope for improved vision and quality of life for individuals living with lazy eye. With early detection and timely intervention, the horizon for a cure for lazy eye is within reach.