Parkinson’s disease is a progressive condition that affects the nervous system and impairs motor function. It affects about 1-2% of people above the age of 60, and currently, there is no cure for it.

Early detection is key to managing the symptoms of Parkinson’s disease, but it can be difficult to identify it early. However, new research has produced promising results for a detection method that uses the patient’s sense of smell to identify Parkinson’s early.

What is Parkinson’s disease?

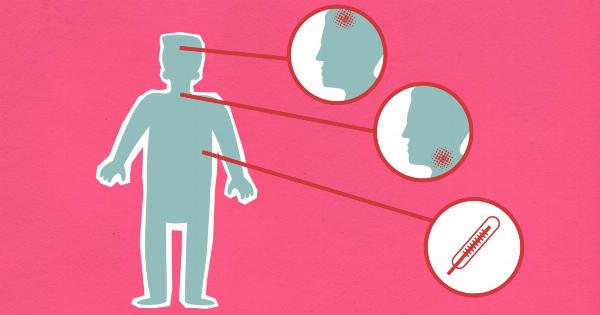

Parkinson’s disease is a disorder of the nervous system that affects movement. It develops when cells in the brain that produce dopamine start to die. Dopamine is a chemical in the brain that helps control movement and coordination.

As dopamine levels decrease, movement can become slow and difficult, leading to the characteristic tremors and stiffness associated with Parkinson’s.

Why is early detection important?

Early detection of Parkinson’s disease is important because it can help to manage the symptoms and delay the progression of the disease.

Parkinson’s disease is difficult to diagnose in the early stages because the symptoms can be subtle and may appear as other conditions. However, early intervention can help patients to better manage their symptoms, maintain their quality of life and possibly slow down the progression of the disease.

Using smell to detect Parkinson’s disease

The idea of using sense of smell to detect Parkinson’s disease is not new. Previous research has suggested that some people with Parkinson’s disease may have a reduced sense of smell, a condition known as hyposmia.

This symptom is thought to be caused by the degeneration of cells in the brain that are involved in both the sense of smell and Parkinson’s disease.

Researchers have recently developed a new test that uses a patient’s sense of smell to detect Parkinson’s disease. The test involves a series of odors being presented to the patient, who is asked to identify the scent.

The test uses a range of odors, including fruits, flowers, and spices. Patients with Parkinson’s disease are found to struggle to identify certain odors, particularly those that relate to fruits and flowers.

How does the test work?

The test, known as the “Sniffin’ Sticks” test, involves presenting the patient with 16 different odors, one at a time. The patient is asked to identify each odor from a list of four options.

The test is quick and non-invasive, taking just a few minutes to complete. Results are usually available immediately after the test.

One of the key advantages of this test is that it is non-invasive and easy to administer. Patients do not need to undergo any painful or invasive procedures, and there are no side effects to worry about.

The test is suitable for people of all ages, and it can be repeated as many times as necessary to confirm a diagnosis.

Promising results

The “Sniffin’ Sticks” test has been shown to be highly accurate in identifying Parkinson’s disease.

In a recent study, researchers tested the sense of smell of 367 participants, including patients with Parkinson’s disease, patients with other neurological conditions, and healthy individuals. They found that patients with Parkinson’s disease had a significantly reduced sense of smell compared to the other groups.

The test was able to identify Parkinson’s disease with high accuracy, correctly identifying the disease in 94% of cases.

These results are highly promising and suggest that the “Sniffin’ Sticks” test could be used as a reliable early detection method for Parkinson’s disease.

Early detection can help patients to better manage their symptoms and improve their quality of life.

Conclusion

The development of a detection method that uses a patient’s sense of smell to identify Parkinson’s disease is a major breakthrough in the field of neurology.

This non-invasive, simple test has the potential to revolutionize how Parkinson’s disease is diagnosed in the early stages. It is highly accurate and reliable, making it an ideal method for early detection.

The “Sniffin’ Sticks” test is still in the early stages of development, but it shows great promise for the future of Parkinson’s disease diagnosis and management.