Amnesia, often portrayed in movies and television as a mysterious condition where individuals lose all memory, has intrigued scientists and neurologists for decades.

While the reality may not be as dramatic as portrayed in the media, amnesia is a complex disorder that can significantly impair a person’s ability to recall past experiences, information, and even their own identity. In this article, we delve into the science behind the memory “vacuum” in amnesia and explore the underlying mechanisms that contribute to this condition.

The Basics of Amnesia

Amnesia is primarily characterized by the profound loss or impairment of memory. It can be caused by various factors, including brain damage, neurological conditions, psychological trauma, or even as a side effect of certain medications or substances.

While there are different types of amnesia, two common forms are anterograde amnesia and retrograde amnesia.

Anterograde Amnesia: The Inability to Form New Memories

Anterograde amnesia is perhaps the most well-known form of amnesia. Individuals with this type of amnesia struggle to create and retain new memories after the onset of the condition.

This can mean that they have difficulty remembering events, people, or even information they have recently encountered. However, their ability to recall memories from before the onset of amnesia, known as retrograde memories, may remain intact.

The impairment in anterograde amnesia can be attributed to a disruption in the brain’s memory consolidation process.

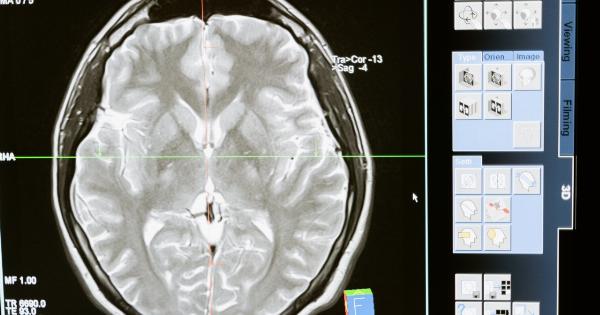

When new information is learned or experienced, it undergoes a complex series of processes within the brain to be stored as a memory. The hippocampus, a key structure in the brain responsible for memory encoding, plays a crucial role in this process.

In individuals with anterograde amnesia, damage to the hippocampus or its connections with other brain regions can prevent the proper consolidation of new memories.

This results in a memory “vacuum” where recent experiences fail to leave a lasting imprint, making it challenging for individuals to form new memories.

Retrograde Amnesia: The Disruption of Existing Memories

While anterograde amnesia primarily affects the formation of new memories, retrograde amnesia is characterized by the inability to remember past experiences or information.

Unlike anterograde amnesia, which often results from brain damage or injury, retrograde amnesia can be triggered by various factors such as psychological trauma or certain medical conditions.

The mechanisms underlying retrograde amnesia are still not fully understood, but it is believed that disruptions occur in the retrieval or access of previously stored memories.

The precise brain regions involved can vary depending on the cause of retrograde amnesia, but typically, damage to areas involved in memory retrieval, such as the medial temporal lobes, can contribute to this condition.

Interestingly, studies have shown that in some cases of retrograde amnesia, memories can gradually return over time.

This phenomenon, known as memory consolidation or reconsolidation, suggests that the brain has the ability to repair or rebuild disrupted or forgotten memories, to some extent.

Neural Pathways and the Memory “Vacuum”

Memory storage and retrieval involve intricate neural pathways and connections within the brain. In both types of amnesia, disruptions to these pathways can contribute to the memory “vacuum” experienced by individuals.

Understanding the neural underpinnings of amnesia is crucial in developing effective treatments and interventions for those affected.

The Role of the Hippocampus

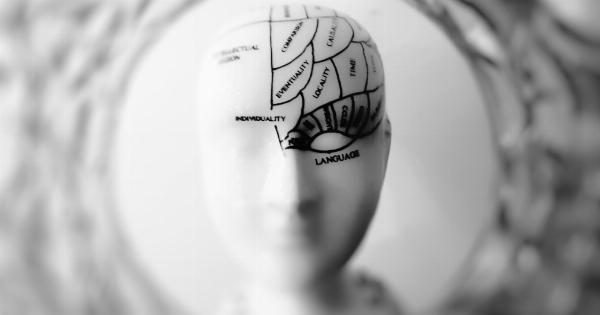

The hippocampus, a horseshoe-shaped structure located deep within the brain, is closely associated with memory formation and consolidation.

Its interaction with other brain regions, such as the prefrontal cortex and amygdala, plays a vital role in transferring information from short-term to long-term memory. Damage to the hippocampus, as seen in cases of anterograde amnesia, disrupts this process.

Researchers have also found that damage to other structures within the medial temporal lobes, where the hippocampus is located, can contribute to memory impairments.

The entorhinal cortex, an area that acts as a gateway to the hippocampus, is particularly important in memory consolidation. Disruptions in this region can hinder the transfer of information and lead to amnesia.

Connecting Memories: The Prefrontal Cortex

The prefrontal cortex, the region of the brain responsible for executive functions and decision-making, also plays a crucial role in memory processes.

It is involved in connecting memories and contextual information, allowing for the retrieval of relevant memories based on the current context. Damage to the prefrontal cortex can impair this connection, contributing to the memory “vacuum” in amnesia.

Studies have shown that individuals with amnesia often have difficulty remembering specific details related to an event or experience.

This can be attributed to the impaired functioning of the prefrontal cortex, which acts as a hub for integrating information and retrieving memories associated with specific contexts or cues.

Memory and Emotional Processing in the Amygdala

The amygdala, a small almond-shaped structure located deep within the brain, is primarily associated with emotional processing and the formation of emotional memories.

It plays a crucial role in attaching emotional significance to events or experiences, which enhances memory consolidation and retrieval.

In cases of amnesia, damage to the amygdala can lead to deficits in emotional processing and memory formation.

This can result in a limited or distorted recall of emotionally significant events, further contributing to the memory “vacuum.” The amygdala’s interaction with the hippocampus and other memory-related regions is vital in forming cohesive and accurate memories.

Treatment Approaches for Amnesia

Treating amnesia can be complex, as it depends on the underlying cause and specific impairments experienced by each individual.

While there is no definitive cure for amnesia, certain interventions and strategies can help manage its symptoms and improve overall cognitive function.

Cognitive rehabilitation, which involves various techniques to enhance memory and cognitive skills, can be beneficial for individuals with amnesia.

This may include memory exercises, external memory aids such as calendars or reminders, and learning strategies to compensate for memory deficits.

Pharmacological interventions have also been explored to aid memory impairments in amnesia.

Medications targeting neurotransmitter systems, such as acetylcholine and glutamate, have shown some promise in enhancing memory restoration or preventing further memory decline. However, their effectiveness can vary depending on the type and severity of amnesia.

Conclusion

Amnesia remains a fascinating and intricate disorder, with much yet to be understood about its underlying mechanisms.

The memory “vacuum” experienced by individuals with amnesia stems from disruptions in the brain’s intricate network of neural pathways involved in memory storage and retrieval. By unraveling the science behind amnesia, researchers and healthcare professionals can work towards developing effective treatments and interventions to improve the lives of those affected by this condition.