Influenza and the common cold are both respiratory illnesses caused by viruses. While they share some similarities, there are distinct differences between the two.

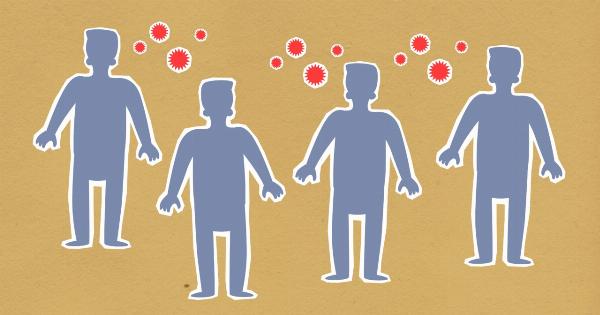

It is uncommon for a person to be simultaneously infected with both influenza virus and a cold virus due to several factors related to the viruses themselves and the human immune response.

1. Types of Viruses

Influenza is caused by influenza viruses, which belong to the orthomyxovirus family. There are three types of influenza viruses: A, B, and C.

On the other hand, colds can be caused by several types of viruses, including rhinoviruses, coronavirus, adenoviruses, and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV).

2. Transmission

The modes of transmission for influenza and cold viruses vary. Influenza is primarily transmitted through respiratory droplets when an infected person coughs, sneezes, or talks.

It can also spread by touching contaminated surfaces and then touching the mouth, nose, or eyes. Colds are mainly spread through direct contact with infected respiratory secretions or by touching contaminated objects and then touching the face.

3. Incubation Period

The incubation period for influenza is usually shorter than that of cold viruses. Influenza symptoms typically appear 1 to 4 days after exposure, with an average of 2 days.

Cold symptoms, however, may take longer to manifest, usually occurring 2 to 3 days after exposure to the virus.

4. Severity of Symptoms

Influenza is generally associated with more severe symptoms compared to the common cold. Influenza symptoms can include high fever, body aches, fatigue, headache, sore throat, and cough.

Colds, on the other hand, typically cause milder symptoms such as a runny nose, sneezing, congestion, and a mild cough.

5. Immune Response

The immune response to influenza and cold viruses differs, making it less common for simultaneous infection. The immune system produces specific antibodies to fight off each virus.

These antibodies are virus-specific, meaning they primarily target the specific virus they have encountered before. The immune response generated against one virus may not be effective against another virus, reducing the likelihood of simultaneous infection.

6. Virus Competition

In some cases, simultaneous infection may occur but is often followed by dominant growth of one virus over the other. When two viruses infect the same host, they compete for the same resources and host cells.

This competition can lead to one virus outcompeting the other, resulting in a more significant presence of one virus and fewer symptoms caused by the other.

7. Seasonal Patterns

Influenza viruses often exhibit seasonal patterns, with peak activity during the winter months. Cold viruses, however, can circulate year-round, with higher prevalence during the fall and winter seasons.

The different seasonal patterns may contribute to a lower likelihood of simultaneous infection.

8. Prevention Measures

The preventive measures used for influenza and colds also contribute to the rarity of simultaneous infection. Influenza vaccines are available and recommended annually, providing protection against specific strains of influenza viruses.

While there is no specific vaccine for the common cold, general hygiene practices such as frequent handwashing, avoiding close contact with infected individuals, and covering the nose and mouth when coughing or sneezing can reduce the risk of both influenza and colds.

9. Diagnostic Testing

Diagnostic testing methods for influenza and colds differ. Rapid influenza diagnostic tests are available to detect the presence of influenza viruses, allowing for prompt treatment and isolation.

Cold viruses, however, are not routinely tested for, as the symptoms are often mild and self-limiting. As a result, simultaneous infection is less likely to be identified through diagnostic testing.

10. Individual Immunity

Finally, individual immunity plays a significant role in preventing simultaneous infection. The immune system’s ability to respond to and eliminate one viral infection can enhance the resistance to other viral infections.

A robust immune response against one virus can reduce the susceptibility to another virus, further decreasing the likelihood of simultaneous infection.